Table of Contents

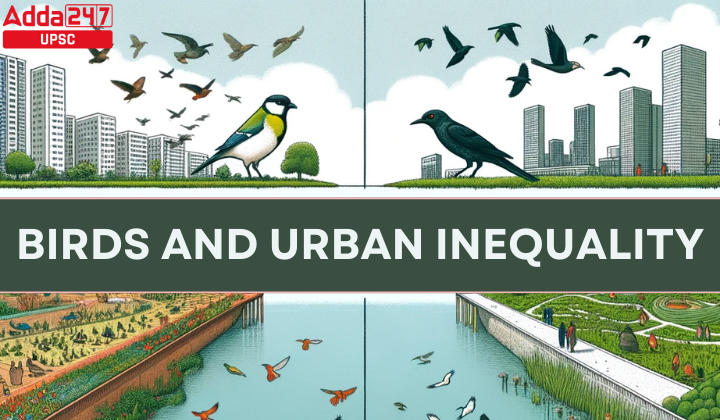

The intricate dance of nature unfolds in the heart of our cities, where wildlife coexists with urban landscapes. Recent studies have shed light on the fascinating links between urban design, structural racism, and their profound impacts on biodiversity, particularly on the avian residents of our cities. In this article, we delve into the groundbreaking research that has unearthed the connections between wealthier neighborhoods, systemic inequalities, and the avian populations that call them home.

Urban Ecology: A Growing Discipline

Urban ecology, a relatively young scientific discipline, has started to gain prominence in recent years. Traditionally, ecologists have focused on rural areas as a counterpoint to cities, overlooking the immense disparities that exist within urban environments.

However, a group of dedicated urban ecologists is now venturing into uncharted territory, exploring the intersection of environmental justice and biodiversity conservation.

Christopher Schell, an ecologist at the University of California, Berkeley, has been at the forefront of this movement.

His study, “Ecological and Evolutionary Consequences of Systemic Racism in Urban Environments,” published in Science 2020, highlights the influence of bigotry and inequality on the way other species experience life in cities.

The Impact of Systemic Inequities

Schell, who grew up in Los Angeles, brings a unique perspective to his research. He emphasizes that systemic inequities—including oppression, residential segregation, gentrification, displacement, unfair zoning laws, homelessness, and more—are what cause urban heterogeneity.

These issues don’t only affect humans; they also have far-reaching consequences for the natural world.

Structural Racism and Civic Design

Schell’s research draws attention to the disparities in urban planning and design. Neighborhoods vary significantly in terms of the number of parks, street trees, and access to green spaces.

The presence of highways, rail lines, or industrial facilities further exacerbates these differences. Schell argues that these disparities are not coincidental but are rooted in systemic racism and historical injustices.

Environmental Justice and Biodiversity

Madhusudan Katti, an ecologist at North Carolina State University, echoes Schell’s sentiments. Katti, who has dedicated his career to studying the intersection of biodiversity conservation and human well-being, emphasizes the alignment of interests between marginalized communities and other species.

He argues against the colonial perspective that separates humans from wildlife, advocating for a more holistic approach that considers both in the urban landscape.

Ecological Fingerprints of Redlining

One pivotal factor contributing to urban inequality and its ecological consequences is redlining, a discriminatory housing policy that dates back to the 1930s.

The Homeowners Loan Corporation (HOLC) graded neighborhoods from A to D based on housing conditions and the racial and economic demographics of residents. The redlined neighborhoods, outlined in red, were labeled “hazardous” for investment.

Lingering Effects of Redlining

Nearly a century later, the legacy of redlining still looms large across many U.S. cities. According to a 2018 study, the majority of redlined neighborhoods are still experiencing financial hardship.

The enduring effects include poverty, unemployment, health disparities, and lost opportunities.

Redlining’s Ecological Legacy

The insidious effects of redlining extend beyond human communities. Urban ecologists are now uncovering the ecological fingerprints of this discriminatory policy.

Redlined neighborhoods often lack green spaces, suffer from higher levels of pollution, and experience limited access to nature. These adverse conditions have far-reaching consequences for local biodiversity, including birds.

Birds as Urban Indicators

Birds, often regarded as the canaries in the coal mine of urban ecosystems, are sensitive indicators of environmental quality. They respond to changes in habitat, food availability, and pollution levels.

Researchers are increasingly focusing on avian populations to understand the complex interplay between urban design, inequality, and biodiversity.

Wealthier Neighborhoods and Avian Diversity

Studies have shown that wealthier neighborhoods tend to host a greater diversity of bird species. The availability of green spaces, lush gardens, and well-maintained parks provides attractive habitats for a wide range of avian residents.

In contrast, impoverished neighborhoods with limited access to greenery experience reduced avian diversity.

Urban Heat Islands and Bird Habitats

One pernicious landscape feature that affects both humans and birds is the urban heat island effect. Wealthier neighborhoods often have more extensive tree cover, which mitigates the impact of heat islands.

Birds benefit from these cooler microenvironments, which can provide essential relief during scorching summers.

Urban Ecology and Environmental Justice

The emergence of urban ecology as a multidisciplinary field offers hope for addressing the intertwined challenges of urban inequality and biodiversity conservation.

Researchers like Christopher Schell and Madhusudan Katti are leading the charge in raising awareness about the interdependence of humans and wildlife within our cities.

Mitigating the Impact of Inequities

Urban ecologists are advocating for a holistic approach to urban planning that considers both humans and wildlife. They stress the importance of mitigating the effects of systemic inequities, such as pollution and limited access to green spaces, to improve the well-being of marginalized communities and protect biodiversity.

Inclusive Civic Design

Creating more inclusive, green, and equitable urban environments can lead to positive outcomes for both people and wildlife.

This includes addressing the historical injustices perpetuated by policies like redlining and ensuring that urban design benefits all residents, human and non-human alike.

Conclusion

As our cities evolve, it is crucial to recognize the intricate connections between urban design, systemic inequalities, and biodiversity conservation. Birds, with their adaptability and sensitivity to environmental changes, serve as valuable indicators of the health of our urban ecosystems.

TSPSC Group 1 Question Paper 2024, Downl...

TSPSC Group 1 Question Paper 2024, Downl...

TSPSC Group 1 Answer key 2024 Out, Downl...

TSPSC Group 1 Answer key 2024 Out, Downl...

UPSC Prelims 2024 Question Paper, Downlo...

UPSC Prelims 2024 Question Paper, Downlo...