Table of Contents

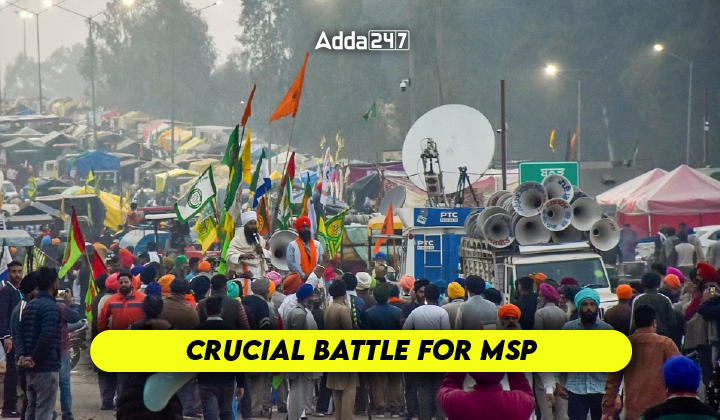

As election fervor heats up, the agrarian distress that has long simmered in India’s rural heartlands is now in the spotlight, with farmers making their grievances heard loud and clear. The symbolic march to the capital’s outskirts is not just a protest; it’s an attempt to steer the national conversation toward the urgent needs of the agricultural sector. The farmers’ march to New Delhi, which commenced on February 13, underscores their persistent demands, notably for a legal assurance regarding Minimum Support Price (MSP) for crops and India’s withdrawal from the World Trade Organization (WTO). These demands reflect their concerns about the impact of international agreements on domestic agricultural policies, particularly in terms of procurement and MSP determination.

A Tug-of-War Over Agricultural Policies

The government’s overture to the farming community, promising to procure diverse crops at Minimum Support Prices (MSP), underscores a desperate bid to quell discontent. However, the conditional nature of these promises—hinging on crop diversification—has done little to pacify the agitating farmers, who argue that their fundamental concerns remain unaddressed.

The Perennial Dilemma of Fair Pricing

At the heart of the farmers’ demands is the assurance of fair pricing for their produce, crystallized in the call for a legal guarantee of MSP. This demand transcends the realm of policy into an ethical imperative, underlining the critical role of MSP in safeguarding India’s food self-sufficiency and rectifying distributional challenges.

Understanding the MSP Mechanism

MSP serves as a critical safety net for farmers, protecting them from the vagaries of market forces that often leave them powerless in price negotiations. Announced for 23 crops and intended to secure remunerative pricing, the MSP’s actual implementation falls short, benefiting a meager 6% of farmers and trapping many in a vicious cycle of debt and despair.

Legal and Regulatory Framework Surrounding Fair and Remunerative Price (FRP) for Sugarcane in India

Fair and Remunerative Price (FRP) is a minimum price set by the Indian government that sugar mills must pay to sugarcane farmers for their produce. It was introduced in 2009 through an amendment to the Sugarcane (Control) Order, 1966, replacing the Statutory Minimum Price (SMP) for sugarcane.

Several factors are taken into account when determining the FRP, including:

- Cost of production of sugarcane

- Recovery of sugar from sugarcane

- Price at which sugar is sold

- Profit from the sale of sugar by-products like molasses, bagasse, and press mud

- Margin for sugarcane growers

- Returns to sugarcane growers from alternative crops

The price is decided by the central government based on recommendations from the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP), as well as in consultation with state governments and the sugar industry.

How to Ensure Legal Minimum Support Price (MSP) for Farmers in India (Continued)

- Implementation Strategies:

- Minor changes to state APMC Acts or the Central Act can establish a legal floor price.

- Investment in backward and forward linkages is crucial. This includes:

- Crop planning and market intelligence for farmers.

- Post-harvest infrastructure for storage, transportation, and processing.

- These linkages will help manage surpluses and prevent “market failures.”

- Addressing Concerns:

- Increasing MSP by 50% is achievable considering existing profit margins.

- Effective procurement and distribution systems, as under the National Food Security Act, can address hunger and ensure MSP.

- PM-AASHA scheme, with its price support mechanisms, could be a model.

- Challenges from WTO can be addressed strategically.

- Impact on Market:

- Legal MSP will increase farmer’s share of consumer prices (currently around 30%).

- Intermediaries’ profit margins might decrease.

- This is seen as a positive step to break free from “free market dogma” and ensure fair farmer income.

A Constitutional and International Backing

The push for a legal MSP guarantee finds resonance not only in India’s constitutional provisions but also in international declarations advocating for farmers’ rights. Surveys indicate overwhelming support among landowners, laborers, and the general public for legalizing MSP, underscoring a widespread recognition of its importance.

State-Level Initiatives and Legislative Efforts

Instances from Maharashtra and Karnataka, along with legislative proposals at both state and national levels, highlight the feasibility of a legal framework for MSP. These precedents demonstrate a growing consensus on the need for robust policy measures to ensure that farmers receive just compensation for their toil.

Conclusion: A Path Forward

The ongoing agitation is a clarion call for a systemic overhaul of India’s agricultural policies, with a legal MSP guarantee at its core. As the nation gears up for elections, the voices of its farmers stand as a testament to the enduring struggle for equity and justice in the agrarian sector. The path to resolution is fraught with challenges, but the collective will of India’s farming community, backed by legal and societal support, may yet pave the way for transformative change.

TSPSC Group 1 Question Paper 2024, Downl...

TSPSC Group 1 Question Paper 2024, Downl...

TSPSC Group 1 Answer key 2024 Out, Downl...

TSPSC Group 1 Answer key 2024 Out, Downl...

UPSC Prelims 2024 Question Paper, Downlo...

UPSC Prelims 2024 Question Paper, Downlo...